Publisher: Micropose

Developer: MPS Labs

Year: 1994

Platform: DOS, Windows, Mac, Linux

Rating: 5

While fantasy-laden adventure games were a dime a dozen in the 80s and 90s, the Micropose team tried really hard to stand out by improving on Sierra’s game design while deploying advanced animation. In those areas, they definitely succeeded with Dragonsphere. While some curious puzzles choices along with some truly awful dialogue and voice acting keep this from being a classic, I still found this adventure compelling.

Twenty years ago, the evil sorcerer Sanwe was locked in his castle by a spell cast by the wizard Ner-Tom, and it’s about to run out. Newly anointed King Callash (that’s you) of Gran Callahach is determined to set out and defeat the sorcerer once and for all. With the aide of your father’s sword, you must seek consult from the leaders throughout your land before facing down Sanwe.

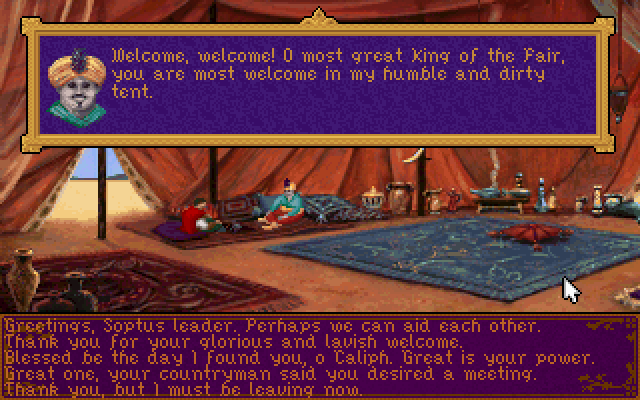

If your eyes rolled back from that cookie-cutter plot, you can be rest assured that it’s simply a placeholder that unravels a deeper and more interesting story than any of the King’s Quest games. While I won’t spoil that, I can say that defeating the sorcerer is only half the battle. Along the way you will need to make friends with the citizens that the crown mostly ignores or despises, including the antagonistic faeries, the desert-dwelling spiritualists, and the deeply distrusted shapeshifters. Only then will you have what it takes to face down Sanwe himself.

While the game is pretty standard point-and-click fare, unique features make this a lot more user-friendly than most games of the time. Most inventory items will have their own assigned verb, eliminating a lot of guesswork. For example, you start the game with a signet ring, that when invoked brings you back to the castle grounds. The verb “invoke” is listed next to the ring; while this could be considered dumbing down the game, there is still need for using standard action verbs (such as “put,” “give,” and “throw”) throughout. I will say I do miss the ability to drag and drop items onto one another to combine them, though there’s only a few puzzles that involved combining items and it’s all rather simple anyhow.

Beyond the cool inventory, there is no way to make the game unwinnable, in a year that Sierra was still pulling that on its customers. You can die, and quite often, but you will always be restored to the most recent safe spot before your fateful decision; thus, the only need to save the game is so you can stop playing. There are plenty of optional points–mostly consisting of procuring treasure– you can lock yourself out of, but it’s hardly worth fretting over.

The world is bright, sharply detailed, and the rotoscoping animation is phenomenal for the time. Whether it’s pulling out your sword, throwing a rat, or climbing a mountain, it all feels smooth and well-realized. The locations are also generally fresh and interesting, from the shapeshifter forest where most of the rocks and trees have various visible body parts, to the crown in the faerie forest that is guarded by several of the most enormous toads you’ve ever seen. Several panoramic shots are also used during cut scenes. The MIDI music is also pleasing to listen to, if not memorable.

The puzzles themselves are a mixed bag. One I really appreciated is in the faerie maze where you must only advance if the magical butterflies approve, lest you be offed. However, not only do you have to figure out which ones tell the truth and which ones lie, their colors change constantly (as do each of their statements). The riddle is not overly complicated, but it was fun to take notes and deduce the answer. There’s also an exceptional puzzle in Sanwe’s castle where you have to figure out how to transport through a magic mirror into a room of fire without burning to death.

Unfortunately, many more are very poorly clued or simply unintuitive. One involving reciting a love poem that likely requires being very familiar with Shakespeare sonnets is particularly frustrating. There’s also a couple of puzzles that require you successfully navigating a long conversation tree AND then also successfully present the correct item to your foe. Any tiny mistake ends in your death, which restores you to the beginning of the conversation. If you don’t intuitively know the answer, the exercise is painfully repetitive. Speaking of repetitive, it is required you win a game of chance with a sheek at least eight times to get various prizes. While there’s a tiny smidgen of strategy involved, it’s no more entertaining than pulling on a one-armed bandit, and slower at that.

Thankfully, I was able to consult a UHS file that helped me solve several puzzles with only gradual hints and I was generally enjoying myself. That is until any character talked for any reason. Most of the actors don’t have any voice work credit outside of Micropose games and it’s clear why. Nearly ever line is delivered with a flat affect, and at no point does it feel like conversations are happening with real people. Characters being surprised, happy, sad, or in love all pretty much sound the same. And though you can turn off the voice acting, the dialogue is so bad it’s barely a reprieve. With few exceptions, the denizens of Gran Callahach speak incredibly deliberately, naming every feeling they’re experiencing and summarizing each conversation as if they’re writing an outro for a middle school essay paper.

The endgame is a mixed bag, including one puzzle that is simply following directions and one that requires you to have discovered something at the very beginning (or be subjected to inventory spamming). However, the granddaddy final puzzle is a delight; while it’s not terribly difficult, I found it quite clever and a satisfying way to resolve the story.

Perhaps with a better writer and a budget for professional actors, Dragonsphere would be hailed as one of the classics of its time. And while its flaws are too numerous to ignore, I would still recommend it to those who love the early 90s King’s Quest or Legend of Kyrandia adventures.