Publisher: EQ Studios

Developer: EQ Studios

Year: 2017

Platform: Windows

Rating: 7

The abandoned mansion/abandoned asylum/abandoned town plot device is beyond overdone. I get why, as having no other characters in your game is a lot easier and cheaper to program. But it still feels amateurish and thus I was hesitant to dive into the first game by indie developer EQ Studios. I needn’t have worried. Rather than going for spooks, The Painscreek Killings goes pure detective mode and does not disappoint.

But first, a musing about the history of puzzles in adventure games. The early text adventures, for the most part, did nothing to hold the player’s hand. Even the well-made ones like Zork and Bureaucracy were brutally difficult with no easy way to get hints. Meanwhile, the early graphic adventures generally had more straightforward puzzles, but were often patently unfair by locking the player out of victory for missing a random item early in the game.

LucasArts recognized this issue and started making it so it was impossible to screw up in their titles. Other designers followed suit, but soon the market for adventure games all but disappeared. It was revived by the indie community in the mid aughts, but in fear of repeating the mistakes of Sierra and to try to lure in a new generation of players, games often became comically easy. Not only could you not screw up, the games held your hand with hotspot highlighters and tasks lists to remind you of your goal, not to mention in-game hints to access.

That’s not to say these were bad developments. When you’re an indie developer and trying to scrape by, the last thing you want is for a player to give up ten minutes into a game and then never show up again. But the move towards easy games led to the walking simulator genre, where puzzles more or less don’t exist and you’re just traveling through a pre-determined story, perhaps making small narrative choices along the way. I love many of these games as well, but I was still craving the difficult puzzles from my youth.

And then within the past ten years, indie developers started figuring out that you could make a gripping adventure with difficult puzzles without holding the player’s hand at all. The first example I can think of is the full-motion video title Her Story in 2015, though it’s possible to win the game by brute force without really solving the puzzle in your head. The Infectious Madness of Dr. Dekker, another FMV game released in 2017 is quite similar in that regard. Return of the Obra Dinn, released in 2018, is when things really hit the ground running for the logic deduction genre, continuing with similar hit titles in Case of the Golden Idol, Duck Detective, and this year’s The Roottrees Are Dead. But the year before that there was a lesser known game called The Painscreek Killings.

While there’s more investigating than deducing here, there’s elements of both. It’s the late 90s and you play a young reporter being sent to the abandoned town of Painscreek right before new developers plan to tear down everything. Several years ago, the beloved mayor’s wife, Vivian Roberts, was brutally murdered in front of her home and the case was never solved. Scott Brooks, the pastor’s son, was arrested for the murder but eventually released due to lack of evidence. Your boss is hoping you can snoop around town and break the case open. You’re given a camera and told to come back in a few days, hopefully with the name of the murderer, their motive, and a picture for the newspaper. Playing in first-person view in a 360 degree environment and starting in the abandoned sheriff’s office outside the city gates you begin your investigation.

Off the bat I’ll admit that both the premise of the investigation and the means by which you unravel it are utterly preposterous. Nearly everything in this town is locked, making your boss’s task seem like punishment. Not only that, if you were allowed to break into things (which seems reasonable given the state of the town), you could solve the mystery in about an hour. Nearly every roadblock in the game involves finding a key or figuring out a numerical passcode.

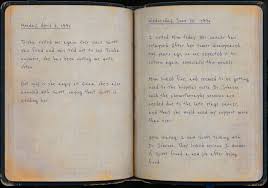

The entire narrative structure is told through newspaper clippings, letters, and journals you find lying about in people’s homes and inside locked rooms and drawers. Hilariously, you will find that suspects will occasionally write down hints to their own combinations. One character in particular has a locked study, a locked desk drawer in the study, a secret room in the study, and another safe elsewhere in the house. Each area has their own separate letters and journals. How helpful!

Caveat aside, the narrative is paced extremely well, especially considering it’s an open world game. While there a few locked areas in the game that are impossible to get into without first solving other puzzles, for the most part you can unravel the story in whatever order your puzzling brain figures out first. Some puzzles have hints in multiple places depending on what order you unravel the mystery. Besides the sheriff’s office, there are a few areas in the game that are immediately accessible, including the cemetery, the hospital, the inn, and the mayor’s mansion. Why the mayor’s mansion with expensive valuables is unlocked but not the post office is a mystery for another day.

The inn itself (the first place I went to) holds a wonderful array of disparate clues from the start. Outside there’s a locked car with a bloody hand print on the glovebox. There’s a voicemail on the answering machine from Oliver, the town’s photographer, telling the proprietor that he’s out of town but the tools he borrowed are in his shop and that Mrs. Patterson has a spare key. There’s a letter and a spare key to an apartment down the road. Underneath room 201 there’s a letter from a proprietor telling Mr. Moss that he owes a late fee and he needs to pay within seven days. And there’s a dart board with a set of rules you can read. None of these clues mean anything to you when you begin, but as you progress and start unraveling town secrets, these clues will be very meaningful.

And so it goes all game long. While the game will record most relevant clues (including journal entries and letters), you are also expected to take photos with your camera of potential evidence or potential passwords. While this is helpful, it’s certainly not enough. About halfway through the game I started my own spreadsheet with a list of all the relevant town denizens, their jobs, and random facts I learned about them. I kept a separate list of locked doors, drawers, and safes that I needed to find keys or codes for as well as other random numbers and dates in hopes that they might be passwords. Reasonable red herrings also abound to keep you on your toes.

You’ll soon find that the mayor’s wife is not the only person in town who died that year. Some of those deaths seem suspicious and some don’t. And while the game doesn’t require you to solve them, your mind will inevitably start creating elaborate scenarios to explain everything. Everyone at first is a reasonable suspect, including the mayor himself, the butler, the gardener, the chauffeur, a couple of the maids, the town’s doctor, and Scott Brooks, the original suspect. The story has so many mysteries beyond just the murder and I was happy to deduce some of them in my head before finding the incriminating evidence.

Many areas of the town remain permanently inaccessible. There is a lot of walking to do, but the town isn’t that large and if you run everywhere it never takes more than twenty seconds or so to get from one end to the other. While you can use a gamepad, I found the mouse and keyboard to be easier as you often have to fine tune the game’s cursor to click on a small item or keyhole.

There’s light background music to supplement the ambient sounds of footsteps, running water, or humming generators. It’s just enough to engage the senses without taking over.

While I was consistently invested from beginning to end, the game does have a few faults that are hard to ignore. The characters could have been drawn out better. While the mystery itself is intriguing, the journals could have included more backstory to give each person more flavor. As it stands, while some characters are more sympathetic than others, I didn’t really care about anyone I was reading about. The writing itself is rather plain; personalities don’t really shine through. The limited voice acting (via answering machines or tape recordings) is also hit and miss.

A few of the puzzles I consider to be unfair. Every time I looked up a hint on-line, I felt no regret. One passcode to a desk drawer in particular is so needlessly complex as to defy all reason. A few times I looked up a hint only to realize that I simply just missed an item that was hiding in plain sight; while I felt silly, given how much ground you have to cover, it’s not unreasonable to miss even a few obvious things. Worse yet, it’s hard to find hints on-line without accidentally learning about something you’re not supposed to know yet.

Some people have decried the endgame. Without spoiling too much, if you find the game’s final clue, the answers to suspect, motive, and murder weapon will be solved for you before the game takes an unexpected (and delightful, at least to me) turn. However, you can win the game without finding the final clue, using the evidence you have to leave town and give your boss your findings.

The Painscreek Killings is definitely not for everybody. While the overall narrative is complex and realistic, the investigation itself frequently ignores the realities of true detective work. However, if you can shut your brain off to that and enjoy the story and the code breaking, you’ll be in for a hell of a time.